THE EMPIRE FROM WITHIN (PART FOUR)

CHAPTERS 20 and 21

Assessments about the options regarding the war in Afghanistan continued. Three priorities in terms of civilian efforts are identified: agriculture, education and reduction of poppies. If these aims were to be met, support for the Taliban could be undermined.

The big question was still: “what can you do in a year?”

Petraeus said he had written a memo called ‘Lessons on Reconciliation’ about his experiences in Iraq and Mullen did not know anything about this.

According to public surveys, two out of every three Americans thought that the president lacked a well-defined plan for Afghanistan. There were even divided opinions in the population about how they should go on.

Axelrod took a breath. The public didn’t distinguish between the Taliban and Al Qaeda. That might be part of the problem.

Only 45 percent of the population was approving Obama´s handling of the war (down 10 points in a month, 15 points since August and 18 points from his peak) The drop was mostly attributable to the loss of Republican support.

Axelrod wasn`t worried; he was saying that finally it would be him or everyone who would explain the decision in a very clear terms so that the people could understand what was being done and why.

Panetta stated that “No Democratic president can go against the military advice, especially if the president had asked for it. His recommendation was to do whatever they were saying. He explained to the other White House officials that in his opinion the decision had to have been taken in one week, but that Obama never asked him and he had never volunteered his opinion to the president.

Former Vice President Dick Cheney stated in public that the U.S. should not dither when their armed forces were in danger.

Obama wanted to decide before his Asian trip. He said that two options had not yet been presented to him, that it was 40,000 troops or nothing. He said that he wanted a new option that same week. In his hand was a two-page memo sent by his budget director Peter Orszag, projecting costs of war in Afghanistan. According to the strategy recommended by McChrystal, the cost during the next 10 years would be $889 billion, nearly 1 trillion dollars.

“This is not what I’m looking for”, said Obama. “I´m not doing 10 years. I´m not doing a long term nation-building effort. I´m not spending a trillion dollars. I’ve been pressing you guys on this”

“That´s not in the national interests. Yes, this needs to be to situation. That is one of the big flaws in the plan that´s been presented to me”.

Gates was backing McChrystal’s request for troops, but for the time being it was necessary to retain a fourth brigade.

Obama said: “We don`t need a fourth brigade”, or the 400,000 troops for the Afghan security forces that McChrystal proposes to train. We could hope for a more moderate growth for this force. We could increase the troops to counteract the enemy expansion but without getting mixed up in a long-range strategy.

Hillary thought that McChrystal should be given what he asked for, but she agreed that they should wait before sending in the fourth brigade.

Obama asked Gates: Do you really need 40,000 troops to push back the Taliban expansion? How about if we send from 15,000 to 20,000? Why wouldn’t it be enough with that number of troops?” He repeated that he didn`t agree with spending a billion dollars or with a counterinsurgency strategy that would go on for ten years.

“I want an exit strategy”, the president added.

Everybody realized that by backing McChrystal, Hillary was uniting forces with the military and with the secretary of the defence, thereby limiting the president`s manoeuvring capacity. The possibilities of hoping for a significantly lesser number of troops or a more moderate policy had been reduced.

It was a decisive moment in her relations with the White House. Was she one to be trusted? Could she ever really belong to the Obama team? Had she ever been a part of his team? Gates thought she was talking from her own convictions.

Soon after, those having similar ideas formed a group. Biden, Blinken, Donilon, Lute, Brennan and McDonough were a powerful group, closest to Obama in many ways and it was a balance facing the united front put up by Gates, Mullen, Petraeus, McChrystal and now Clinton.

CHAPTERS 22 & 23

Obama summoned the Chiefs of Staff to the White House. During the last two months the uniformed military had been insisting on sending 40,000 troops, but the individual services chiefs still hadn`t been consulted. The army, navy, marines and air force chiefs were the ones recruiting, training, equipping and supplying the troops for commanders like Petraeus and his subordinate chiefs in the field such as McChrystal. These last two did not attend because they were in Afghanistan.

Obama asked them to propose three options to him.

James Conway, commander general of the Marines, referred to the combatants’ allergies to extended missions that went on further than the defeat of the enemy. His recommendation was that the president should not get mixed up in a long-range operation for the building of a nation.

Gen. George Casey, Army chief of staff, said that the scheduled withdrawal in Iraq would permit the Army the army to have 40,000 men ready for Afghanistan, but that he felt skeptical about the great commitments of troops in these wars. For him, the key was a rapid transition, but that the plan of 40,000 was a global risk acceptable to the army.

The chief of naval operations and the air force chief had little to say, because whatever the decision on Afghanistan, the impact on their forces would be minimal.

Finally Mullen presented the president three options:

1. 85,000 troops. This was an impossible number. Everyone knew that they didn’t have this force.

2. 40,000 troops

3. Between 30,000 to 35 000 troops

The hybrid opinion was 20,000 men or two brigades to disperse the Taliban and train Afghan troops.

CHAPTERS 24 and 25

Obama proposes to the president of Pakistan an escalation against the terrorist groups operating from his country.

The CIA director said he was hoping for full support from Pakistan since Al Qaeda and its followers were a common enemy. He added that it was a matter of Pakistan’s very survival.

Obama was realizing that the key to keeping the national security team together was Gates.

After returning from Asia, Obama called his national security team and he promised them that he would make his final decision in two days. He said he agreed with less ambitious but more realistic objectives, and that said objectives should be attained in a shorter period of time than what had been initially recommended by the Pentagon. He added that the troops would start thinning out after July 2011, the time frame Gates had suggested in their last session.

“We do not need perfection; four hundred thousand is not going to be the number we were going to be at before we started thinning out”.

Hillary seemed to be almost jumping in her seat, showing every sign she wanted to be called on, but Jones had determined the speaking order and the secretary would have to sit through Biden’s comments.

Biden had issued a memorandum that took the president up on his offer to question the strategy’s time frame and objectives. Petraeus felt the air go out of the room.

Biden wasn’t sure that the number 40,000 was sustainable from the political point of view and he had many questions about the feasibility of the elements of the counterinsurgency strategy.

Clinton had her chance to speak. She was fully backing the strategy. “We spent a year waiting for an election and a new government. The international community and Karzai all know what the outcome will be if we don’t increase the commitment. What we’re doing now will not work. The plan was not everything we all might have wanted. But we won’t know if we don’t commit to it. I endorse this effort; it comes with enormous cost, but if we go halfhearted we’ll achieve nothing”. Her words were a very common phrase that she used when she was the First Lady in the White House and one she still regularly used: fake it until you make it.

Gates proposed waiting until December 2010 in order to make a complete assessment of the situation. He believed that July was too soon a date for that.

Via video-conference from Geneva, Mullen was supporting the plan and said that it was necessary to send troops as quickly as possible, that he was sure that the counterinsurgency strategy would bring results.

Seeing that a bloc in favour of sending the 40,000 troops was being aligned, the president spoke. “I don’t want to be in a situation here where we’re back here in six months talking about another 40,000”.

“We won’t come back and ask for another 40,000”, said Mullen.

Petraeus stated that he was supporting any decision made by the president. And after having stated his unconditional support, he declared that his recommendation, from a military point of view, was that the objectives couldn’t be attained with less than 40,000 troops.

Peter Orzag said that probably they would have to ask Congress for additional funding.

Holbrooke agreed with what Hillary had said.

Brennan assured them that the antiterrorist program would continue independently of any decision that was made.

Emmanuel referred to the difficulty in asking Congress for additional funding.

Cartwright said that he supported the hybrid option of 20,000 troops.

The president tried to summarize. “At the end of two, the situation may still have ambiguous elements”, he said. He thanked them all and announced that he would be working on this on the weekend in order to make a final decision at the beginning of the coming week.

On Wednesday, November 25, Obama got together in the Oval Office with Jones, Donilon, McDonough and Rhodes. He said he was inclined to approve sending 30,000 troops but that this decision wasn’t final.

“This needs to be a plan about how we’re going to hand it off and get out of Afghanistan. Everything we are doing has to be focused on how we are going to get to the point where we can reduce our footprint. It’s in our national security interest. It has to be clear that this is what we are doing”, said Obama. “American people, they are not as interested in things like the numbers of brigades. It’s the number of troops. And I’ve decided on 30,000.

Obama now appeared more certain about the numbers of men.

“We need to make clear to people that the cancer is in Pakistan. The reason we’re doing the target (…) in Afghanistan is so that the cancer doesn’t spread there. We also need to excise the cancer in Pakistan”.

The figure of 30,000 seemed to be fixed. Obama commented that from a political point of view it was easier for him to say no to 30,000 since that way he could devote himself to the national agenda, something he wanted to be the lynch pin of his term in office. But the military didn’t understand that.

“Politically, what these guys don’t get is it’d be a lot easier for me to go out and give a speech saying (…) the American people are sick of this war, and we are going to put in 10,000 trainers because that how we’re going to get out of there.” But “the military would be upset about it”.

It was apparent that a part- perhaps a large part- of Obama wanted to give precisely that speech. He seemed to be road-testing it.

Donilon said that Gates might resign if the decision was only the 10,000 trainers.

“That would be the difficult part”, said Obama, “because there’s no stronger member of my national security team”.

The president decided to announce the 30,000 in order to keep the family together.

CHAPTERS 26 & 27

On November 27, Obama again invited Colin Powell to his office for another private talk. The president said he was struggling with the different points of view. The military was unified supporting McChrystal’s request for 40,000 more troops. His political advisors were very skeptical. He was asking for new approaches, but he just kept getting the same old options.

Powell told him: “You don’t have to put up with this. You are the commander in chief. These guys work for you. Because they are unanimous in their advice doesn’t make it right. There are other generals. There’s only one commander in chief”.

Obama considered Powell to be a friend.

The day after Thanksgiving, Jones, Donilon, Emmanuel, McDonough, Lute and Colonel John Tien, an Iraq combatant veteran, went to see the president in his office. Obama asked why they were meeting with him again to deal with the same matter. “I thought this was finished Wednesday”, he stated.

Donilon and Lute explained to him that there were still some questions from the Pentagon that hadn’t been answered and they wanted to know whether the 10 percent increase to the number of troops, including the facilitators, had been accepted.

Exasperated, the president said it hadn’t, that only 30,000 had been, and he asked the reason for that meeting after everyone had been in agreement. The president was told that they were still working on the military. Now they wanted the 30,000 troops to be in Afghanistan by summer.

It seemed that the Pentagon was again opening up one of the topics. They were also questioning the date of the troops withdrawal (July 2011). Gates preferred that it should happen six months later (the end of 2011).

“I’m pissed”, Obama said, but he didn’t raise his voice much. It looked like all the topics were going to be discussed, negotiated or cleared up again. Obama told them that he was willing to take a step back and accept sending 10,000 trainers. And that would be the final numbers.

This was the controversy facing the president and the military system. Donilon was amazed to see the political power being exercised by the military but he realized that the White House had to be the long-distance runner in this contest.

Obama continued to work with Donilon, Lute and the others. He began to precisely dictate what he wanted, drawing up what Donilon called a “terms sheet”, similar to the legal document that is used in a business transaction. He agreed that the strategic concept of the operation would be ‘degrade’ the Taliban, not dismantling it, or defeating or destroying it. He pasted the six military missions from the memo required to revert the Taliban momentum.

But the civilians at the Pentagon and the General Staff tried to expand the strategy.

“You can’t do that to a president”, Donilon would tell them. “That wasn’t what Obama wanted. He wanted a narrower mission”. But the pressure contiunued.

“Put in restrictions”, Obama ordered. But when Donilon returned from the Pentagon he would come back with more additions, not less. One of them was to send a message to Al Qaeda. “We’re not going to do it”, said the president when he found out.

Donilon felt like he was rewriting the same orders ten times over.

Requests for collateral missions kept pouring in from the Pentagon. Obama kept on saying “no”.

Some of them continued to support McChrystal’s original request for 40,000 troops. It was as if nobody had said “no” to them.

“No”, said Obama. The final figure was 30,000, and he held on to the troop pull-out date of July 2011, the same date to begin the transfer of responsibility for security to the Afghan troops.

His orders were typed on six single-spaced pages. His decision was not just to make a speech and refer to the 30,000; this would also be a guideline, and everybody would have to read and sign it. That was the price he was going to insist on, the way in which he wanted to put an end to the controversy –at least for the time being. But as we all know now, the controversy, just like the war, probably wouldn’t end, and the struggle would continue.

November 28 was another day dedicated to the National Security Council, a meeting where Donilon and Lute took part. The analysis of the strategy became the centre of the universe. The president and all of them were being overwhelmed by the military. The questions made by the president or anyone else no longer mattered. Now the only feasible solution was the 40,000 troops.

Donilon was wondering how many of those pressing for that option would be around to see the effects of the strategy in July 2011.

The conclusion was that all of them would leave and the president would remain here along with everything these guys had sold him.

The debate was still going on –in his house and in his head. Obama sounded like he was back to tentative on the 30,000 troops. He asked for his team’s opinion. Clinton, Gates and John weren’t present.

Colonel Tien told the president that he didn’t know how he was going to defy the military chain of command. “If you tell McChrystal, I got your assessment, got your resource constructs, but I’ve chosen to do something else, you’re going probably to have to replace him. You can’t tell him, just do it my way, thanks for your hard work, do it my way”. The colonel meant that McChrystal, Petraeus, Mullen and even Gates were ready to quit, something unprecedented in high ranking military circles.

Obama knew that Brennan was against a large troop increase.

Obama had inherited a war with a beginning, a middle part, but without any clear-cut ending.

Lute was thinking that Gates was too deferential with the uniformed military. The secretary of defence is the president’s first civilian line of control. If the secretary wasn’t going to guarantee that control, the president was going to have to do it. Lute thought that Gates wasn’t serving the president very well.

The president phoned up Biden and told him that he wanted to meet with the whole national security team on Sunday in the Oval Office. Biden asked to meet with him first and Obama told him “no”.

To be continued tomorrow.

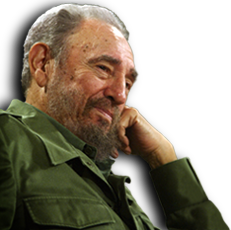

Fidel Castro Ruz

October 13, 2010

5:14 p.m.